Female Affirmative Approach to Assessments

RMC embraces a Feminist perspective and Rainbow Mandala Clinic is acutely aware of the challenges highlighted below , and is committed to ensuring our assessments and engagement are collaboratively undertaken with respect, validation, and trauma-informed care.

Of the upmost importance is truly embracing the Female perspective , her own perspective of living with undiagnosed ADHD or AuDHD, and possibly anxiety and/or depression.

Feminist Approach to our Assessments

Despite some progress, women continue to face a heightened risk of being dismissed as “the worried well” when disclosing experiences of distress to healthcare professionals.

Without appropriate recognition, women who experience mental distress within contexts of gender inequality may be left with increased guilt and shame unless their accounts are met with belief, acceptance, and validation.

Women also consistently report that, alongside professional knowledge about the intersections between gender inequality and distress, they require healthcare professionals to demonstrate genuine kindness and a non-judgemental stance when supporting them to share painful experiences.

A Feminist-Informed Approach to Adult ADHD Assessment

Many adults—especially women and gender-diverse people—reach adulthood without an ADHD diagnosis, despite years of struggle. This is rarely due to a lack of symptoms. More often, it reflects how ADHD has traditionally been defined, recognised, and assessed.

A feminist-informed approach is about fairness, accuracy, and respect for lived experience.

Your Experience Matters

Your clinician treats your own understanding of your life as meaningful clinical information. ADHD does not always look the same on the outside as it feels on the inside.

You do not need to have:

- Been disruptive at school

- Failed academically

- Appeared “obviously hyperactive”

Feeling mentally restless, overwhelmed, emotionally reactive, or exhausted from constantly holding things together is real and valid.

ADHD Doesn’t Always Match the Stereotype

Many people—particularly women—were:

- Quiet, compliant, or high-achieving

- Seen as anxious, sensitive, or perfectionistic

- Praised for coping, while privately struggling

A feminist-informed assessment recognises that appearing capable often requires enormous effort.

Masking Is Recognised, Not Penalised

Masking means working very hard to appear organised, calm, or functional, even when things feel chaotic inside. This often develops in response to strong expectations to be:

- Responsible

- Emotionally regulated

- Attentive to others’ needs

In assessment, masking is understood as effort and adaptation, not evidence that ADHD is absent.

Looking at the Whole of Your Life

Rather than relying only on school reports or childhood behaviour, your clinician will explore:

- How much effort everyday life has always taken

- Whether things feel harder than they “should”

- Times when coping became unsustainable (e.g. parenting, work pressure, burnout, menopause)

Difficulties often increase as life demands grow—not because you’ve failed, but because your brain is being asked to do more than it can sustainably manage.

ADHD Can Co-Exist with Anxiety, Trauma, or Burnout

Many people are first diagnosed with anxiety, depression, or emotional regulation difficulties. A feminist-informed approach recognises that these experiences can develop alongside undiagnosed ADHD, rather than excluding it.

Coping for years without support does not mean ADHD isn’t present.

A Collaborative and Transparent Process

Your clinician will:

- Clearly explain how ADHD is assessed

- Invite questions and shared decision-making

- Use questionnaires as tools, not pass/fail tests

- Consider identity, life stage, and context

The aim is understanding—not judgement.

Diagnosis as Understanding

If ADHD is diagnosed, we share with you our philosophy:

- An explanation, not a label

- A way to make sense of long-standing patterns

- A foundation for support, treatment, and self-compassion

- the life changing benefits of prescribed ADHD medication

Many people describe feeling relief—not because something is “wrong,” but because something finally makes sense.

Under diagnosis of ADHD in Women

Written by Phil, RMC Clinical Director & Social Work Practitioner

For too many years, women with ADHD have been routinely dismissed, disregarded,

and misdiagnosed when they pursue evaluations and diagnoses for impairments like distractibility, executive dysfunction, and emotional dysregulation. Completely missed for decades has been the lack of understanding of the impact of declining estrogen on the the intensity of ADHD symptoms.

As estrogen drops—especially in the luteal phase, postpartum, or perimenopause—dopamine and norepinephrine levels also decrease. For people with ADHD, who already struggle with dopamine regulation, this can make everything harder: memory, focus, emotional control, even motivation.

Estrogen plays a key role in modulating neurotransmitters like dopamine. So when levels drop, ADHD symptoms (especially emotional dysregulation and executive dysfunction) often spike.

- The ADHD Women’s Wellbeing podcast

- The Emotional lives of Girls with ADHD. By Dr Lotta Skoglund Video

- Stigma & Unique Risks for Girls & Women with ADHD By Dr Hinshaw Video

- Late Diagnosis and Adult-Onset ADHD

- Article : Why ADHD in Women is Routinely Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Treated Inadequately

- Journal Articles relevant to this area

Article : Morgan, J. (2023). Exploring women’s experiences of diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood: a qualitative study. Advances in Mental Health, 22(3), 575–589. - A UK study of 2200 patients found that adult ADHD is more complex than a straightforward continuation of the childhood disorder, with 70% of individuals with adult ADHD never having a diagnosis in childhood.

Under-recognition in childhood:

Morgan (2023) and large-scale studies such as Moffitt et al. (2015) and Agnew-Blais et al. (2016) show that up to 70% of adults with ADHD were never diagnosed in childhood. This challenges the traditional view of ADHD as simply a continuation of a childhood disorder.

Adult-onset ADHD exists:

The Dunedin longitudinal study (Moffitt et al., 2015) demonstrated that many adults met diagnostic criteria at age 38 without ever showing ADHD symptoms in childhood. This suggests that ADHD symptoms can emerge later, or that childhood symptoms may have been masked, subtle, or overlooked.

Gender parity in adulthood:

Childhood ADHD diagnoses are far more common in boys (ratios as skewed as 5:1). However, in adulthood, the prevalence evens out, with men and women being diagnosed at roughly equal rates (approx. 4.4% of adults overall). Some adult clinical series even report female predominance.

Despite extensive research on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD) in girls and women, many clinicians continue to get it wrong — misattributing symptoms of ADHD in females to anxiety, mood disorder, or even hormones.

A History of Injustice

1. Diagnostic Criteria

DSM-5 (2013) requirement: Symptoms must be present before age 12. For many women, retrospective recall or historical documentation (e.g., school reports, parent reports) is unreliable, leading to “false negatives.”

- Historical injustice: Because ADHD symptoms in girls often went unnoticed or were misinterpreted, adults may lack a documented childhood history of impairment, even though symptoms were present.

2. Gender Bias in Assessments

- Male-oriented frameworks: Early ADHD research and assessment tools were normed primarily on boys, emphasising externalising behaviours like hyperactivity and impulsivity.

- Female presentation overlooked: Girls more often show internalising symptoms (inattentiveness, daydreaming, disorganisation) that do not fit the stereotypical “hyperactive boy” profile.

3. Socialisation and Masking

- Normative feminine behaviours: Girls are often socialised to be compliant, quiet, and “people-pleasing.” These behaviours can conceal ADHD traits.

- Masking and compensation: Many women develop strong coping strategies or deliberately camouflage difficulties to fit in, which reduces likelihood of early recognition.

- Mental health costs: Chronic masking is associated with increased anxiety, depression, and reduced self-esteem.

4. Co-occurring Diagnoses and Misattribution

- Diagnostic overshadowing: When depression, anxiety, or eating disorders are present, ADHD symptoms may be mistakenly attributed to those conditions.

- Treatment first bias: Mental health conditions (especially mood and anxiety disorders) are often treated without exploring underlying ADHD, delaying accurate diagnosis.

5. Referral and Rater Bias

- Teachers’ perceptions: Teachers are more likely to refer disruptive boys than inattentive girls, even when impairment is equivalent or greater in the girls.

- Parent reports: Parents may not interpret symptoms as clinically significant in girls if academic achievement or social compliance is maintained.

- Informant bias: Research shows consistent underreporting of girls’ symptoms compared to boys, particularly from teachers.

6. Distinct Female Symptom Profile

- Prominent inattentive features: Forgetfulness, difficulty sustaining attention, poor organisation, and distractibility tend to dominate in girls/women.

- Less externalising behaviour: Hyperactivity and impulsivity are often subtler, expressed as internal restlessness rather than overt disruption.

- Functional impairment overlooked: Academic underachievement, chronic stress, or exhaustion may be dismissed as personality traits rather than ADHD.

7. Coping and Delayed Recognition

- Adaptive strategies: Girls may work harder to maintain performance (e.g., perfectionism, over-preparation, excessive reliance on routines).

- Breakdown in adulthood: As life demands increase (workload, parenting, household management), these strategies become unsustainable, leading to functional impairment and eventual recognition of ADHD.

Importance of Female Hormones in ADHD

Front. Glob. Women’s Health, 07 July 2025

Text below is directly from the published study listed above.

Hormonal transitions exacerbate ADHD symptoms and mood disturbances, yet pharmacological research and tailored treatments are lacking.

Executive function deficits manifest differently in girls and women with ADHD and are influenced by neuropsychological and neurobiological profiles.

Diagnostic practices and sociocultural factors contribute to delayed diagnoses, increasing the risk of comorbidities, impaired functioning, and diminished quality of life.

Undiagnosed women have increased vulnerability to premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression, and cardiovascular disease during perimenopause.

ADHD is not only diagnosed less frequently in girls than boys, but also at a later age (3–5). Often, women with ADHD seek help for other mental health difficulties such as anxiety or depression, rather than ADHD, leading to delayed or missed ADHD diagnoses (4, 6, 7).

Compared to male individuals, females with ADHD face higher risks of co-occurring neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions, use of psychiatric medications and healthcare services (5, 8, 9).

Many risks are worsened with late or missed diagnosis, including teenage pregnancy, risky sexual behaviour, self-harm or eating disorders (10). Late diagnoses also adversely impact relationships, mental health, confidence, and self-esteem in women (11).

Several factors result in delayed diagnosis, including diagnostic practices (e.g., male-biased criteria that may miss female manifestations) and sociocultural reasons (e.g., gendered expectations and masking symptoms (12), and access to inadequate services (13).

Women with ADHD often adhere strongly to social norms, using compensatory strategies to mask their symptoms. While these mechanisms help them cope temporarily, they can lead to missed diagnoses, accumulation of secondary comorbid symptoms, and diminished self-esteem (14).

A formal ADHD diagnosis is essential for accessing self-education and other support (e.g., educational or workplace) and treatment (e.g., stimulant medication), which significantly improve long-term outcomes (15–17). However, girls and women are less likely to receive ADHD medications even when diagnosed (3, 18, 19).

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and ADHD

Hergüner et al. (2015) investigated ADHD symptoms in a group of 40 females with PCOS, a common endocrine condition associated with hyperandrogenism, compared to a control group of 40 females without PCOS. In females with PCOS, Hyperactivity, and Total adult ADHD symptoms scores (ASRS), as well as childhood symptoms of Behavioral Problems/Impulsivity , were significantly increased compared to females without PCOS.

Together, these studies suggest some relationship between endogenous sex hormones and ADHD symptoms in females.

ADHD and Sex Hormones in Females: A Systematic Review: Summary

Osianlis, E., Thomas, E. H. X., Jenkins, L. M., & Gurvich, C. (2025). ADHD and Sex Hormones in Females: A Systematic Review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 29(9), 706-723

Journal of Attention Disorders (2025)

HER Centre Australia, Department of Psychiatry, School of Translational Medicine,

Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

Theories surrounding a hormonal influence on ADHD suggest sex hormones are likely to modulate neurotransmitters including dopamine, as well as serotonin and noradrenaline (Haimov-Kochman & Berger, 2014). This may provide a mechanism to explain exacerbation of ADHD symptoms during periods of hormonal fluctuation, such as menopause and across the menstrual cycle.

Lower and fluctuating estrogen levels may therefore impact regulation of dopamine synthesis and activity. Given the existing dysregulation of dopaminergic pathways in ADHD, further fluctuations may exacerbate mechanisms of ADHD pathophysiology, and/or alter the efficacy of stimulant medication, leading to an increased severity of ADHD symptoms during times of hormonal change, such as the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

More recently, sex and gender differences in ADHD have been recognised, and demonstrate a likely underdiagnosis of ADHD in females in childhood and adulthood, rather than a male disposition to ADHD (Faraone et al., 2024)

Females typically present with internalising symptoms of ADHD including inattention, as well as additional symptoms not included in the diagnostic criteria but associated with ADHD, such as executive dysfunction and emotional dysregulation.

Alternatively, males, and particularly younger males/boys present with more externalizing symptoms including hyperactivity; as these symptoms are more observable to teachers and caregivers, they may reinforce sex-based perceptions of ADHD being more common in males, as they conform with typical characterizations of ADHD based on males (Mowlem et al., 2019; Young et al., 2020).

In this sense, the traditional conceptualization of ADHD centered around male presentation is challenged by presentation in females, and contributes to the under recognition of ADHD in females. Comorbid mental health symptoms are also highly prevalent in people with ADHD (Choi et al., 2022), and specifically females with ADHD, which may further contribute to misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of ADHD in females (Ottosen et al., 2019; Young et al., 2020).

Interest has recently grown regarding sex differences in ADHD, including research specifically exploring ADHD presentation and underlying mechanisms in females. Endogenous sex hormones have been identified as one factor that may contribute to the sex differences in ADHD symptoms.

Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone are thought to play a key role in cognition and many psychiatric and neurodevelopment conditions (Gurvich et al., 2018).

In females, fluctuations of estrogen and progesterone have been directly implicated in conditions including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression, and menopausal depression (Hantsoo & Epperson, 2015; Kulkarni et al., 2024).

Other mental health conditions such as schizophrenia have also shown hormonal effects, with exacerbation of symptoms at times of low estrogen, and demonstrated improvement of symptoms with hormonal therapy (Brzezinski et al., 2017).

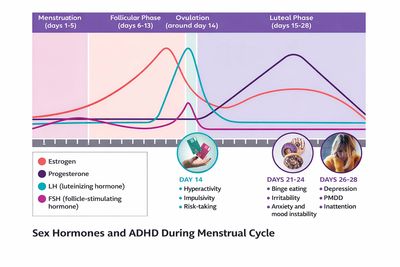

The Menstrual Cycle

Oestrogen

Exists in three key forms in females:

- estrone (E1; primary estrogen during menopause)

- estradiol (E2; primary estrogen during reproductive years)

- estriol (E3; primary estrogen during pregnancy).

Progesterone

The second key sex hormone in females and follows the same patterns of estrogen, increasing from childhood into reproductive years, and falling to very low levels in menopause, shown in Figure 1. Androgens such as testosterone are also present in females, though estrogen and progesterone are considered the key hormones in females.

Estrogen and progesterone act directly on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to modulate release of hormones, and effect regulation of monoamines including serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline, which are involved in cognition and behavior (Del Río et al., 2018)

The Key Mechanism

- Oestrogen → supports dopamine activity

(helps focus, working memory, motivation, emotional regulation) - Progesterone → can counteract dopamine effects

(may increase sedation, emotional reactivity, brain fog)

When oestrogen drops or progesterone dominates, ADHD symptoms often worsen.

Medication Considerations

- Stimulants rely on dopamine → reduced oestrogen can blunt effect

- Challenges:

- Shorter duration of benefit premenstrually

- Increased side effects or emotional rebound

- Cycle-aware treatment planning can be helpful

Women with ADHD are more sensitive to hormonal fluctuations

ADHD symptoms :

✅improve during high-estrogen states : mid-cycle, pregnancy, hormone therapy

🚩worsen during low-estrogen states : luteal phase, postpartum, perimenopause, menopause

The combined drop in both systems during perimenopause/menopause explains why many women experience a significant surge in ADHD-related challenges alongside mood disorders.

Ovarian Hormones and the Brain

- Estrogen and progesterone are produced primarily in the ovaries, but also in smaller amounts elsewhere (e.g., adrenal glands, fat tissue).

- Both hormones cross the blood–brain barrier and bind to receptors in regions important for mood regulation, memory, attention, and executive function.

- Estrogen boosts dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex and striatum—areas heavily implicated in ADHD. This is why higher estrogen often means improved attention, motivation, and mood stability.

- Progesterone, on the other hand, has more inhibitory effects on the brain and can dampen dopamine activity, potentially worsening ADHD symptoms in certain phases.

Menstrual Cycle Phases and ADHD

✅Follicular Phase (Day 1–14):

- Estrogen levels rise steadily, peaking around ovulation.

- Many women with ADHD notice better focus, energy, and emotional stability in this phase.

🚩Luteal Phase (Day 15–28):

- Progesterone rises, estrogen drops sharply then stabilizes at a lower level.

- This hormonal shift often worsens PMS/PMDD symptoms: anxiety, irritability, low mood, fatigue, cognitive fog, binge eating, and sleep problems.

- Women with ADHD are disproportionately affected by PMDD, likely because of dopamine system vulnerability.

Menstrual Cycle Stages & ADHD

- Estrogen is the hormone responsible for the sexual and reproductive development of girls and women.

- Estrogen also modulates functioning of many psychologically important neurotransmitters, including: ✅dopamine, which plays a central role in ADHD and executive functioning

✅acetylcholine, which is implicated in memory

✅serotonin, which regulates mood

- Higher levels of estrogen are linked to enhanced executive function and attention.1 Low or fluctuating estrogen levels are associated with various cognitive deficits and with neuropsychiatric disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and depression.2

- Levels of estrogen and other hormones fluctuate considerably across the lifespan and impact the mind and body in numerous ways.

- The complexity of hormonal fluctuations complicates the research into how hormones affect cognition — particularly in women with ADHD

- Estrogen concentration is high and steady in the reproductive years. In the monthly menstrual cycle, estrogen levels steadily rise during the follicular phase (usually from day six to 14) and drop precipitously in ovulation (around day 14).

- In the latter half of the luteal phase (the last two weeks of the cycle) estrogen levels continue to drop as progesterone increases. If pregnancy does not occur, both estrogen and progesterone levels drop, and the thickened uterine wall sheds during menses. Women report emotional changes and cognitive problems at various points in the cycle, especially when estrogen levels are at their lowest.3

- These hormonal fluctuations in the menstrual cycle impact ADHD symptoms.4In the follicular phase, as estrogen levels are increasing, ADHD symptoms are at their lowest.4

- Indeed, in some studies, neurotypical females report greater stimulant effects during the follicular phase than during the luteal phase.5

- The luteal phase is when we see premenstrual syndrome (PMS) – a collection of physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms brought on by decreasing estrogen levels and increasing progesterone. Interestingly, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a severe version of PMS, is more prevalent in women with ADHD than it is in women without ADHD.

- The climacteric years, the transition from the reproductive years through menopause, is characterized by enormous hormonal fluctuations as overall estrogen levels gradually decrease. These fluctuations contribute to physical and cognitive changes.

Perimenopause

Front. Glob. Women’s Health, 07 July 2025

Volume 6 - 2025

Text below is directly from the published study listed above:

- It is understandable that when oestrogen is low or declining in an individual in whom important neurotransmitters such as dopamine are already low or dysregulated, these 'shortages' reinforce each other.

- Thus, women with ADHD may experience increased impairment in their mood, cognition, memory, sleep, and other domains of functioning.

- Given the impact of hormonal fluctuations on mood, cognition, and overall functioning, individualised treatment strategies—such as:

1) optimising stimulant dosages across menstrual phases (49)

2) and/or offering SSRIs (50)

3) and/or hormonal therapy (51)

may improve symptom management.

Menopause

Jean Hailes for Women’s Health

- Menopause is when your periods stop due to lower hormone levels. Most women go through menopause between the ages of 45 and 55, but it can happen earlier or later. This can be because of lifestyle or your family’s health history. It might also be because of other medications, such as cancer treatments and contraceptives.

- Perimenopause is when you have symptoms of menopause, but your periods have not completely stopped. You reach menopause when you have not had a period for 12 months.

- Perimenopause and menopause can affect your physical, emotional, and social well-being. It can cause challenging symptoms that can change and last from 4 to 12 years.

- The symptoms of perimenopause and menopause can have a big impact on your daily life. If can impact your relationships, family, social and work life.

- There are over 34 symptoms of menopause, and everyone’s journey is different.

- The changes to your hormones at this time can impact your mental health. You may feel overwhelmed, stressed and anxious.

- Common physical symptoms can include hot flushes, heart palpitations, joint pains and vaginal dryness.

- Many women also have trouble sleeping. Lack of sleep and tiredness can also make these symptoms worse.

- Before menopause, our hormones protect our bones, hearts, and brain. After menopause, the risk of osteoporosis, heart disease and dementia increases. Some medicines can replace the missing hormones and help relieve your symptoms.

- Before menopause is the perimenopause stage, when periods become irregular – in duration (short vs. long intervals) and flow (heavy vs. light) – but have not yet stopped. The median age for the onset of perimenopause is 47, and it can last four to 10 years.7

- During this stage, total estrogen and progesterone levels begin to drop irregularly. Levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which stimulate the ovaries to produce estrogen, and luteinizing hormone (LH), which triggers ovulation, also vary considerably.

- FSH and LH levels initially increase as estrogen levels drop (fewer follicles remain to be stimulated), eventually decreasing substantially and remaining at low levels in postmenopause. OB/GYNs often measure FSH and LH levels to determine if a patient is in menopause.

- These fluctuating estrogen levels help explain the sometimes extreme mood and cognitive problems that many women, ADHD or not, experience in the lead up to menopause.8

- During menopause, menstrual cycles stop due to declining levels of estrogen and progesterone. The onset of menopause is 12 months after the last period, and it signals the end of a woman’s reproductive years. The stage following menopause is referred to as postmenopause.

The median age for menopause is 51.9

- Declining estrogen levels are associated with various changes across all menopause stages. These symptoms can worsen and improve over time, though most physical symptoms stop after a few years.

- There is no available research on menopause and ADHD specifically, but plenty of anecdotal evidence supports a link between the two. Many of my patients with ADHD report that pre-existing symptoms worsen in menopause. Some patients also report what appears to be a new onset of symptoms, though I find that many of these patients were “borderline” or “mildly” ADD throughout most of their life.

- Furthermore, research has not yet established how often ADHD is diagnosed for the first time during menopause – an important facet to consider, given that menopause and ADHD in later adulthood share many symptoms and impairments, including but not limited to:

- mood lability, poor attention/concentration, sleep disturbances, depression

- These similarities imply an overlap in clinical presentation, and possibly in underlying brain mechanisms.

- studies found that atomoxetine and Vyvanse improve executive functioning in healthy menopausal women,11 12 and that the latter, as shown by neuroimaging, activates executive brain networks.13

- These findings suggest that some women may benefit from ADHD medication to treat cognitive impairments during menopause.

PMDD & PMS

Clark, K., Fowler Braga, S., Dalton, E. (2021). PMS and pmdd: Overview and current treatment approaches. US Pharm, 46(9), 21-25.

- PMS involves common, milder premenstrual symptoms with limited functional impact.

- PMDD is a severe, cyclical mood disorder characterised by predictable monthly impairment and full inter-episode recovery.

Key distinction: PMDD is driven primarily by affective and behavioural symptoms, not physical symptoms alone.

PMDD & PMS

Dr Lewis and Dr Res have extensive experience supporting women with dosing adjustments of ADHD

medication at different stages of their menstrual cycle.

Tracking Apps:

- Article. PMS and PMDD : current treatment approaches. US Pharm, 46(9), 21-25.

- PMDD & ADHD link: recognising & treating video

- Female-specific pharmacotherapy in ADHD: premenstrual adjustment

- Article: Prevalence of hormone-related mood disorder symptoms in women with ADHD

- Article: ADHD & Sex Hormones

- PMDD & ADHD link: recognising & treating video

- PMDD by Royal College of Nursing video

PMDD and PME are diagnosed through daily symptom tracking, along with tracking your menstrual cycles. Daily symptom tracking will show you and your doctor if your symptoms arise in your premenstrual/luteal phase (PMDD), worsen in your premenstrual/luteal phase (PME), or occur throughout your cycle without a noticeable worsening in the premenstrual/luteal phase (not PMDD or PME).

There is not yet a blood, hormone, or saliva test to diagnose PMDD or PME. However, such tests can help rule out hormone imbalances or vitamin deficiencies that mimic PMDD or PME. The DSM-5 and ICD-11 state that daily symptom tracking for at least two menstrual cycles is required for diagnosis.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and PMDD are chronic, hormone-based conditions, often life-changing for sufferers.

Clinical implications of increasing stimulant dosage premenstrually include improved control of ADHD and mood symptoms, leading to better focus, energy, productivity, and emotional stability.

Adjustments should be:

- Based on cycle awareness (using PMDD calendars or apps)

- Individualised in dosing and timing

- Monitored for response and side effects (minimal or absent in many cases)

- Applicable to several types of psychostimulants

Research has not yet explained the disproportionate link between ADHD, PMDD, and postpartum mood disorders. Current science suggests women with ADHD may be more sensitive to hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle and after childbirth.

Follicular Phase (First Half)

The average menstrual cycle is about 28 days. During the first two weeks—the follicular phase—estrogen levels rise steadily, while progesterone remains low. Estrogen enhances dopamine and serotonin activity, which can boost mood and cognitive performance.

Many women with ADHD report that symptoms and stimulant effectiveness vary during this phase. For some, the high-estrogen environment can improve functioning, as estrogen and dopamine potentiate each other.

For others—particularly those with impulsivity and hyperactivity—these surges may heighten risky or sensation-seeking behaviours, sometimes making medication doses feel “too strong.”

Studies suggest that overall, the follicular phase is smoother for women with ADHD than the luteal phase, which follows.

Luteal Phase (Second Half of Cycle)

During the third and fourth weeks—the luteal phase—progesterone levels rise as estrogen falls sharply and then stabilises at a lower level. Progesterone can counteract estrogen’s beneficial brain effects, often reducing stimulant medication efficacy.

Clinical evidence indicates that women may find their ADHD medication less effective in this low-estrogen state, due to reduced dopamine activity. Dr Lewis and Dr Res have extensive experience supporting women with dosing adjustments in this phase, frequently recommending short-acting stimulant formulations to offset symptom worsening.

Tailoring medication dosages to hormonal status—known as cycle dosing—can optimise treatment. Tracking your cycle provides powerful insights into how hormonal fluctuations affect ADHD symptoms, medication response, and overall functioning.

PMDD & ADHD

1. Hormones as a stress amplifier, not the primary pathology

PMDD reflects abnormal CNS sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations, which amplifies pre-existing neurodevelopmental and trauma vulnerabilities.

2. Predictable cyclicity is the diagnostic anchor

- PMDD symptoms are time-locked to the luteal phase

- There is clear functional recovery post-menses

Failure to track cycles is the most common cause of misdiagnosis.

3. High risk of mislabelling

Without cycle mapping, presentations are often misdiagnosed as:

- Major depressive disorder

- Bipolar II disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- “Poor coping” in ADHD or autism

4. ADHD/autism increase PMDD severity—not prevalence

Neurodivergent individuals are not more likely to develop PMDD, but often experience:

- Greater severity

- Earlier functional impairment

- Higher misdiagnosis rates

Clinical Take-Home Summary

PMDD is best conceptualised as a cyclical neuroendocrine trigger that temporarily destabilises executive functioning, emotional regulation, sensory tolerance, and trauma-related threat systems—with full inter-episode recovery.

Emotional Presentation

Anxiety & ADHD

Article: Lifetime co-occurring psychiatric disorders in newly diagnosed adults with

ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder. (2020)

Video : Anxiety & ADHD: How they are related By Dr Barkley

Perfectionism & ADHD & Anxiety By Dr Sharon Saline video

Emotional Dysregulation & Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria

By Dr William Dodson Video (60 mins)

ADHD & Social Anxiety

By Dr Sharon Saline

Article: Females with ADHD: a lifespan approach in girls and women.

BMC Psychiatry (2020)

Article: Annual Research Review: ADHD in girls and women: underrepresentation,

longitudinal processes, and key directions.

Stephen P. Hinshaw. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (2021)

Article: Adverse experiences of women with undiagnosed ADHD and the invaluable role of diagnosis.

Holden, E., Kobayashi-Wood, H. Sci Rep 15, 20945 (2025).

Article: ADHD and Sex Hormones in Females: A Systematic Review .

J Atten Disord. 2025 Apr 18;29(9):706–723.

Article : Exploring Female Students’ Experiences of ADHD and its Impact on Social, Academic, and Psychological Functioning.

J Atten Disord. 2023 Aug;27(10):1129-1155.

ADHD in women and girls is frequently overlooked when anxiety or depression is present, because ADHD symptoms—especially inattention, restlessness, and emotional lability—are misattributed to the mood or anxiety disorder. Women with ADHD have a high likelihood of also experiencing anxiety disorders (generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, or phobias).

Studies estimate that 25–50% of women with ADHD meet criteria for at least one anxiety disorder at some point. Undiagnosed and untreated ADHD can frequently lead to a secondary presentation of general anxiety , triggered by the consequences , in home and work life, of challenges with procrastination, distractibility, time management, planning and setting and following through on priorities.

Frequently Woman are often treated first for anxiety and/or depression, delaying recognition of the under diagnosed ADHD.

Emotions & Rejection Sensitivity

The 7 Truths about Emotions & ADHD Video by Dr William Dobson

Managing Rejection Sensitivities in Real Time video By Dr Sharon Saline

How ADHD shapes perception, motivations & emotions Video by Dr William Dobson

Managing big emotions in ADHD Video by Dr Sharon Saline

Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in ADHD Video by Dr Barkley

Article: 3 Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks

Article: Exaggerated Emotions: How and Why ADHD Triggers Intense Feelings

Article: Rejection Sensitivity Is Worse for Girls and Women with ADHD

Article: How ADHD Ignites RSD: Meaning & Medication Solutions

Article: New Insights Into Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

Article: RSD Vs Bipolar Disorder

Rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD) is an intense vulnerability to the perceptio — not

necessarily the reality — of being rejected, teased, or criticised by important people

in your life. RSD causes extreme emotional pain that may also be triggered by a sense

of failure, or falling short — failing to meet either your own high standards or others’

expectation.

Dysphoria is the Greek word meaning unbearable; its use emphasizes the severe physical and

emotional pain suffered by people with RSD when they encounter real or perceived

rejection, criticism, or teasing.

The response is well beyond all proportion to the nature of the event that triggered it.

Rejection sensitive dysphoria is not a formal diagnosis, but rather one of the most

common and disruptive manifestations of emotional dysregulation—a common but

under-researched and oft-misunderstood symptom of ADHD, particularly in adults.

RSD is a brain-based symptom that is likely an innate feature of ADHD.

Often, this intense emotional reaction is hidden from other people. People

experiencing it don’t want to talk about it because of the shame they feel over their lack

control, or because they don’t want people to know about this intense vulnerability.

Test for Rejection Sensitivity

An ADHD guide to Emotional Dysregulation & Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria

By Dr William Dodson Video

Rejection Sensitivity & Social Anxiety

By Dr Sharon Saline Video

How RSD presents

Internalised RSD:

Presents as sudden, intense sadness that can imitate a major mood disorder, sometimes with suicidal ideation. This rapid shift in mood is often misdiagnosed as rapid-cycling bipolar disorder or major depressive episodes.

Externalised RSD:

Manifests as instantaneous rage toward the person or situation perceived as rejecting

Can be mistaken for anger dysregulation or oppositional behavior.

Anticipatory RSD:

Leads individuals to constantly scan for potential rejection, even when uncertain.

May resemble social phobia, though the core fear is different

Social Anxiety Vs Rejection Sensitivity:

Social phobia: fear of public humiliation or negative scrutiny.

RSD: fear of losing love, approval, or respect.

Subjective Experience:

People often struggle to put RSD into words. They describe it as Intense, Awful, Terrible, Overwhelming

The emotional reaction is consistently tied to a perceived or real loss of approval, love, or respect.

Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD) & ADHD

Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD) & ADHD

Dr Lewis has a specialisation in the psychiatric treatment of combined ADHD and Bipolar Affective Disorder, and has 27 years of experience of psychiatric treatment of Bipolar 1 disorder and Bipolar 2 disorder.

An ADHD guide to Emotional Dysregulation & Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria

By Dr William Dodson Video

https://youtu.be/yipQQk2iALQ?si=6vVmtc_8JSgDtPFq

https://youtu.be/52GqJJdosxQ?si=wUQPUguNnzlH1ipD

https://youtu.be/ibPRV_DocmQ?si=-bJFN1eFVNl2dj-Z

Bipolar was formerly called manic-depressive illness or manic depression.

Bipolar Affective Disorder & ADHD share 14 features in common.Two studies, the STAR*D program

and the STEP-BD program, both found a tremendous overlap between the disorders.

For clients with bipolar disorder, there is a 40% chance of having ADHD as well.

ADHD:

With adult ADHD, you see a very di!erent pattern; the moods of an individual with

ADHD are clearly triggered. The ADHD symptoms of rejection sensitive dysphoria, for example,

is triggered by the perception that a person has been rejected, teased, or criticised.

An observer might not be able to point out the trigger, but the individual

with ADHD can say, “When my mood shifts, I can always see a trigger.

My mood matches my perception of the trigger.” In technical terms, ADHD moods are “congruent.”

Mood changes are instantaneous and intense in individuals with ADHD, much

more so than in a neuro-typical person.

ADHD moods rarely persist for more than a few hours. It is extremely

rare for them to last two weeks. Typically, the mood can be altered by

the person with ADHD finding a new interest or occupation that

captures their interest and distracts them from the intense emotion.

Bipolar Mood Disorder:

Unlike ADHD, bipolar is a classic mood disorder that has a life of its own separate from

the events of a person’s life, outside of the person’s conscious will and control.

Bipolar moods aren’t necessarily triggered by something; they just come and they stay.

Usually, the onset is very gradual over a period of weeks to months.

To meet the bipolar definition, the mood must be continuously present for at least

two weeks and then its resolution must be gradual over a period of weeks to months.

Depression and anxiety are often the most visible coexisting conditions experienced by women who have ADHD. Both conditions can be present as separate disorders or as the result of struggling with undiagnosed or poorly treated ADHD for a very long time.

The two conditions frequently prompt women to seek medical and mental health care and can lead to a diagnosis of ADHD.

When treating a woman or girl who has ADHD and a co-occurring condition, the clinician or treatment specialist needs to address the condition causing the most difficulty at that moment, especially conditions that can be life-threatening if untreated.

Pregnancy

Dr Lewis and Dr Res have extensive experience supporting women with stimulant medication during pregnancy and post-pregnancy

Article: Patterns of ADHD Medication Usage During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

(Harvard Medical School Research)

Article: Course of ADHD During Pregnancy and the Postpartum

(Harvard Medical School Research)

Article: ADHD as a Risk Factor for Postpartum Depression and Anxiety

Article: The Course of ADHD During Pregnancy

Articles

- AuDHD: why Autism is so difficult to diagnose in girls & women with ADHD Video

- Divergent Voices YouTube Channel video

- Autism & Eating Disorder Challenges video by Divergent Voices

- Autism & ADHD video by Divergent Voices

- Could I be on the Autism Spectrum ? video

- Overlook traits of Autism in Women video

- Late Autism Diagnosis in Women video by Divergent Voices

- Website Inside Out (Eating Disorder)

- AFRID explanation. Avoidant Food Restriction Disorder

- Professor Sandra Kooji (expert in Female ADHD): Hormones, ADHD & Research video

- Webinar Video :Impact of Hormones on Lives of Girls & Women with ADHD

- Journal Articles relevant to this area

- Article: Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Front Neurosci. 2015 Feb 20;9:37.

- Article : Examining the Link Between ADHD Symptoms and Menopausal Experience.(2025)

- Article : Female ADHD: lifelong interplay of hormonal fluctuations with mood, cognition & disease(2025)

- Video Regret & Resolve: How Women can transform the challenges of a late diagnosis of ADHD. By Dr Kathleen Nadeau

- Video :Midlife : Interaction of hormones & ADHD in Women

- Talking with your Dr about ADHD & Menopause video by Dr Lotta Skoglund

- Menopause & ADHD : How estrogen impacts dopamine & women’s health video

Women’s Healthcare clinics

https://www.hermatters.com.au/

https://hhanda.com.au/about-us

https://evocawomenshealth.com.au/locations/belconnen/

https://www.shfpact.org.au/index.php/appointments/our-services ( bulk billed )

https://ochrehealth.com.au/medical-centre-kingston/services/?service=womens-health

Guidelines & Frameworks : Menopause

Preventive Activities over the Life-Cycle – Adults:

Lifecycle chart by Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice 10th edition (Red book)

Australian Guideline References for Menopause :

- Australasian Menopause Society. (2022). AMS guide to managing the menopause. https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/gp-hp-resources

Clinical guidance on diagnosis, hormonal variability, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and treatment considerations.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2017). Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (9th ed.).

RACGP. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/red-book

Includes preventive health considerations across the reproductive lifespan and post-menopause.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2024). Menopause.

In RACGP Handbook of Non-Drug Interventions (HANDI). https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/handi

Primary-care focused Australian guidance on menopause recognition and management.

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2020).

Management of the menopause. RANZCOG. https://ranzcog.edu.au

Specialist-level guidance on menopausal physiology, hormonal change, and clinical management.

National Health and Medical Research Council. (2014). Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of menopause. NHMRC.

References for Data Shown:

- Harlow, S. D., Gass, M., Hall, J. E., et al. (2012). Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10 (STRAW+10). Menopause, 19(4), 387–395.

- Santoro, N. (2016). Perimenopause: From research to practice. Menopause, 23(3), 200–207.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Menopause. WHO fact sheets.

- National Institutes of Health. (2025). Peri- and postmenopause—Diagnosis, symptoms, and interventions. NIH PMC article.

- Mayo Clinic. (2025). Perimenopause symptoms and causes. Retrieved from MayoClinic.org.

References: PMDD

References for PMDD

Epperson, C. N., Steiner, M., & Hartlage, S. A. (2012). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for a new category for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(5), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302

Girdler, S. S., Lindgren, M., Porcu, P., Rubinow, D. R., Johnson, J. L., Morrow, A. L. (2012). A history of depression enhances sensitivity to GABAergic neurosteroids during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(7), 1136–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.004

Hantsoo, L., & Epperson, C. N. (2015). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Epidemiology and treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(11), 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0628-3

Harrison, A. J., Long, K. A., & Powers, T. A. (2021). Emotion regulation strategies in autistic adults: The role of sensory sensitivity and stress. Autism, 25(4), 1041–1052. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320985130

Kleinstäuber, M., & Witthöft, M. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 106, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.12.010

Martel, M. M. (2009). A new perspective on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Emotion dysregulation and trait models. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(9), 1042–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02105.

Rapkin, A. J., & Lewis, E. I. (2013). Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Women’s Health, 9(6), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.2217/whe.13.52

Rubinow, D. R., & Schmidt, P. J. (2019). Sex differences and the neurobiology of affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(1), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0148-z

References For Perimenopause & Menopause

Burger, H. G., Dudley, E. C., Robertson, D. M., & Dennerstein, L. (2002). Hormonal changes in the menopause transition. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 57, 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1210/rp.57.1.257

Grumbach, M. M. (2002). The neuroendocrinology of human puberty revisited. Hormone Research, 57(Suppl. 2), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/00005809

Hale, G. E., Zhao, X., Hughes, C. L., Burger, H. G., Robertson, D. M., & Fraser, I. S. (2007). Endocrine features of menstrual cycles in middle and late reproductive age. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(10), 3817–3824. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0066

Hall, J. E. (2015). Endocrinology of the menopause. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 44(3), 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.001

Maki, P. M., & Henderson, V. W. (2016). Hormone therapy, dementia, and cognition. Endocrine Reviews, 37(4), 372–403. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1108

Nelson, H. D. (2008). Menopause. The Lancet, 371(

9614), 760–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60346-3

Parent, A. S., Teilmann, G., Juul, A., Skakkebaek, N. E., Toppari, J., & Bourguignon, J. P. (2003). The timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity. Endocrine Reviews, 24(5), 668–693. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2002-0019

Prior, J. C. (1998). Perimenopause: The complex endocrinology of the menopausal transition. Endocrine Reviews, 19(4), 397–428. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv.19.4.0333

Santoro, N., & Randolph, J. F. (2011). Reproductive hormones and the menopause transition. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 38(3), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.004

Simpson, E. R. (2003). Sources of estrogen and their importance. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 86(3–5), 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00360-1

Soares, C. N. (2019). Mood disorders in midlife women: Understanding the critical window and opportunities for prevention. Menopause, 26(7), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001322

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.