ADHD in more detail

Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often experience significant challenges in self-management, including organisation, planning, initiating and completing tasks in a timely manner, shifting between activities, self-monitoring, and inhibiting responses.

Article: A second mental health presentation along with ADHD

These skills are collectively described as executive functions (EFs), which can be viewed as “those self-directed actions needed to choose goals and to create, enact, and sustain actions toward those goals” (Barkley, 2012).

When executive functions are impaired, individuals typically struggle with reduced productivity, inefficiency, missed deadlines, poor planning, disorganisation, “careless” errors, and frequent loss or forgetting of items. For some—particularly those with the combined presentation of ADHD—reduced inhibitory control can also manifest as emotional dysregulation and inappropriate verbal or physical behaviour in interpersonal contexts.

Over the lifespan, these difficulties contribute to repeated failures to achieve goals personally, academically, and occupationally. Such persistent struggles often increase the risk of secondary anxiety and depression, which are highly prevalent in adults with ADHD.

Clinical Framing: Executive Functioning Deficit Disorder

Our diagnostic clinical assessment is undertaken through a semi-structured clinical interview, which explores ADHD symptoms as manifestation of executive functioning deficits.

ADHD is understood as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by executive dysfunction, impairing the brain’s ability to select, monitor, and regulate behaviour in pursuit of goals.

Executive dysfunction affects:

- Task management and planning

- Time awareness and scheduling (time blindness)

- Goal setting and persistence

- Concentration and resistance to distraction

- Working memory, organisation, and self-monitoring

- Self-inhibition and attentional shifting

From this perspective, ADHD is best conceptualised as a disorder of self-regulation rooted in EF impairment.

Misleading Terminology

The term “Attention Deficit” is misleading, as it obscures the broader self-regulatory impairments that characterise ADHD. Similarly, “Hyperactivity”—while valid in describing childhood behaviour—does not capture the adult presentation. Adults are not “hyperactive” in the same way as an 8-year-old boy; instead, impulsivity better reflects the adult clinical profile. Impulsivity has clear potential for negative consequences in decision-making, relationships, and occupational functioning.

Gender Bias and Diagnostic Inadequacy

Current diagnostic criteria and terminology are insufficient and discriminatory when applied to women and adolescent girls. Symptoms in these groups often manifest less in disruptive behaviour and more in internalised difficulties such as disorganisation, emotional dysregulation, rejection sensitivity, and cognitive/verbal impulsivity. These differences have contributed to widespread under-recognition and late diagnosis in women.

A more accurate diagnostic approach reframes ADHD as a broader Executive Functioning Self-Regulation Deficit Disorder, particularly in women, encompassing:

- Emotional dysregulation and rejection sensitivity

- Cognitive, verbal, and behavioural impulsivity

- Persistent executive functioning challenges across domains

Brain & ADHD

1. Prefrontal Cortex (the “control centre”)

This is the front part of the brain responsible for:

- Focus and attention

- Planning and organisation

- Working memory (holding information in mind)

- Inhibiting impulses

In ADHD, this area tends to be under-activated or less efficiently regulated by dopamine. As a result, a person may:

- Know what they need to do but struggle to start

- Lose track of tasks or instructions

- Act before thinking, especially under stress

This is why ADHD is often described as a “doing” problem, not a knowing problem.

2. Basal Ganglia (motivation and reward)

The basal ganglia help:

- Regulate movement and restlessness

- Decide what feels rewarding

- Filter distractions

This system relies heavily on dopamine. In ADHD, dopamine signalling here is less consistent, which can lead to:

- Difficulty sustaining effort for tasks with delayed reward

- A strong pull toward novelty, urgency, or stimulation

- Restlessness or feeling “driven” to move

This helps explain why motivation in ADHD is interest-based rather than importance-based.

3. Anterior Cingulate Cortex (task switching and effort regulation)

This area helps with:

- Monitoring effort

- Switching between tasks

- Noticing mistakes and adjusting behaviour

In ADHD, this system can struggle to stay “online,” leading to:

- Getting stuck (task paralysis)

- Difficulty shifting attention

- Feeling mentally exhausted by tasks others find simple

4. Cerebellum (timing, coordination, and regulation)

The cerebellum is involved in:

- Timing and sequencing

- Coordination (physical and cognitive)

- Regulating emotional and mental pace

Differences here can contribute to:

- Poor sense of time (“time blindness”)

- Difficulty estimating how long tasks will take

- Feeling rushed or, alternatively, stuck

5. Brain network communication (not just one area)

Importantly, ADHD is not caused by a single faulty brain part. It reflects differences in how these regions communicate with each other—especially through dopamine pathways.

When dopamine levels are optimal (for example, during highly interesting or urgent tasks), these networks often work extremely well, which explains periods of intense focus or creativity (sometimes called hyperfocus).

In summary

ADHD involves differences in brain systems responsible for:

- Executive functioning (planning, focus, self-control)

- Motivation and reward

- Emotional regulation

- Time perception

Rejection Sensitivity Explained (part 1)

Rejection sensitivity (often termed Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria, RSD) describes a pattern of intense emotional pain and rapid mood shifts triggered by perceived or actual rejection, criticism, or failure.

While not a formal DSM diagnosis, it is commonly observed in adolescents and adults with ADHD and has clear neurobiological and developmental correlates.

Core features

- Disproportionate emotional response (e.g., shame, sadness, anger) to minor criticism or neutral feedback

- Rapid onset and intensity, often described as overwhelming or unbearable

- Threat-based interpretation of social cues (e.g., assuming disapproval or abandonment)

- Behavioural consequences: avoidance, people-pleasing, withdrawal, rumination, or sudden anger

Why it occurs in ADHD

- Emotion regulation deficits: ADHD involves reduced top-down modulation from prefrontal networks, limiting the ability to dampen emotional responses once triggered.

- Heightened limbic reactivity: Increased sensitivity of threat-detection systems (e.g., amygdala) amplifies perceived social threat.

- Learning history: Repeated experiences of criticism, failure, or misunderstanding (especially in undiagnosed ADHD) condition strong emotional responses to feedback.

- Dopaminergic vulnerability: Fluctuations in reward and motivation systems increase sensitivity to social evaluation.

Clinical presentation

- Marked distress after feedback, even when constructive

- Perfectionism or overcompensation to avoid criticism

- Interpersonal instability driven by fear of rejection

- Overlap with anxiety, mood symptoms, and trauma histories, increasing diagnostic confusion

Key clinical distinctions

- Not the same as social anxiety (anticipatory fear dominates)

- Not a personality disorder (responses are state-dependent, rapid, and context-linked)

- Often improves with ADHD-targeted treatment (psychoeducation, skills, and—where appropriate—medication)

Management implications

- Psychoeducation to normalise and externalise the response

- Emotion regulation strategies (e.g., pause-and-label, cognitive reappraisal)

- ADHD-informed psychotherapy (CBT/DBT-informed approaches)

- Medication optimisation for ADHD symptoms, which may reduce emotional reactivity

Rejection Sensitivity Detail (part 2)

The 7 Truths about Emotions & ADHD Video by Dr William Dobson

Managing Rejection Sensitivities in Real Time video By Dr Sharon Saline

How ADHD shapes perception, motivations & emotions Video by Dr William Dobson

Managing big emotions in ADHD Video by Dr Sharon Saline

Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in ADHD Video by Dr Barkley

Article: 3 Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks

Article: Exaggerated Emotions: How and Why ADHD Triggers Intense Feelings

Article: Rejection Sensitivity Is Worse for Girls and Women with ADHD

Article: How ADHD Ignites RSD: Meaning & Medication Solutions

Article: New Insights Into Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

Article: RSD Vs Bipolar Disorder

Rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD) is an intense vulnerability to the perceptio — not

necessarily the reality — of being rejected, teased, or criticised by important people

in your life.

RSD causes extreme emotional pain that may also be triggered by a sense

of failure, or falling short — failing to meet either your own high standards or others’

expectation.

Dysphoria is the Greek word meaning unbearable; its use emphasizes the severe physical and

emotional pain suffered by people with RSD when they encounter real or perceived

rejection, criticism, or teasing.

The response is well beyond all proportion to the nature of the event that triggered it.

Rejection sensitive dysphoria is not a formal diagnosis, but rather one of the most

common and disruptive manifestations of emotional dysregulation—a common but

under-researched and oft-misunderstood symptom of ADHD, particularly in adults.

RSD is a brain-based symptom that is likely an innate feature of ADHD.

Often, this intense emotional reaction is hidden from other people. People

experiencing it don’t want to talk about it because of the shame they feel over their lack

control, or because they don’t want people to know about this intense vulnerability.

Test for Rejection Sensitivity

An ADHD guide to Emotional Dysregulation & Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria

By Dr William Dodson Video

Rejection Sensitivity & Social Anxiety

By Dr Sharon Saline Video

How RSD presents

Internalised RSD:

Presents as sudden, intense sadness that can imitate a major mood disorder, sometimes with suicidal ideation. This rapid shift in mood is often misdiagnosed as rapid-cycling bipolar disorder or major depressive episodes.

Externalised RSD:

Manifests as instantaneous rage toward the person or situation perceived as rejecting

Can be mistaken for anger dysregulation or oppositional behaviour .

Anticipatory RSD:

Leads individuals to constantly scan for potential rejection, even when uncertain.

May resemble social phobia, though the core fear is different

Social Anxiety Vs Rejection Sensitivity:

Social phobia: fear of public humiliation or negative scrutiny.

RSD: fear of losing love, approval, or respect.

Subjective Experience:

People often struggle to put RSD into words. They describe it as Intense, Awful, Terrible, Overwhelming

The emotional reaction is consistently tied to a perceived or real loss of approval, love, or respect.

Rejection Sensitivity & the Brain (part 3)

Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria (RSD) in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

reflects altered neural processing of :

social threat, emotional salience, and regulation, rather than a discrete diagnostic entity.

It arises from functional and connectivity differences across fronto-limbic, salience, and reward networks.

1. Amygdala: Heightened Threat Detection

The amygdala plays a central role in detecting threat and assigning emotional salience, particularly to social cues such as criticism, exclusion, or perceived disapproval.

- In ADHD, the amygdala demonstrates hyper-reactivity to emotionally salient stimuli

- Neutral or ambiguous interpersonal cues may be misinterpreted as rejection or failure

- This contributes to the rapid onset and intensity of emotional pain characteristic of RSD

Importantly, this response is fast and reflexive, occurring before higher-order cognitive appraisal.

2. Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): Impaired Top-Down Regulation

The prefrontal cortex—particularly the dorsolateral (dlPFC) and ventromedial (vmPFC) regions—modulates emotional responses generated by the limbic system.

In ADHD:

- Reduced PFC activation limits inhibitory control over amygdala output

- Emotional responses are less filtered, less contextualised, and harder to down-regulate

- Individuals may intellectually “know” a response is disproportionate but cannot dampen it in real time

This explains why RSD is often described as overwhelming, uncontrollable, and physically painful.

3. Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): Pain and Social Error Processing

The anterior cingulate cortex integrates emotional pain, cognitive conflict, and social evaluation.

- The ACC is involved in both physical pain and social pain processing

- In ADHD, ACC dysregulation contributes to:

- Intensified distress following perceived rejection

- Heightened sensitivity to interpersonal mistakes or disapproval

- Persistent rumination on social “errors”

This shared circuitry helps explain why rejection in RSD is often described as visceral rather than merely

4. Dopaminergic Reward Pathways: Salience Without Stability

ADHD is associated with dopaminergic dysregulation in fronto-striatal circuits, including the nucleus accumbens.

- Dopamine modulates reward prediction, motivation, and emotional salience

- In ADHD, inconsistent dopamine signalling leads to:

- Over-weighting of negative feedback

- Reduced buffering from prior positive experiences

- Difficulty maintaining emotional equilibrium after criticism

As a result, rejection signals carry disproportionate motivational and emotional weight.

5. Default Mode Network (DMN): Internalisation and Rumination

The default mode network, active during self-referential thought, shows atypical regulation in ADHD.

- Increased DMN intrusion during emotional states promotes:

- Self-blame (“I’ve failed”, “I’m not good enough”)

- Retrospective replay of social interactions

- Prolonged emotional activation after the triggering event

This sustains RSD responses well beyond the initial interpersonal cue.

Integrated Neurobiological Model of RSD in ADHD

RSD reflects the convergence of:

- Hyper-reactive threat detection (amygdala)

- Insufficient top-down emotional inhibition (PFC)

- Amplified social pain signalling (ACC)

- Dopaminergic salience imbalance

- Excessive self-referential processing (DMN)

Together, these systems produce rapid, intense, and enduring emotional responses

to perceived rejection, often without conscious control.

Clinical Implications

- RSD is not a character flaw or over-sensitivity

- It represents a neurodevelopmentally mediated emotion-regulation vulnerability

- Effective management often requires:

- ADHD-specific pharmacotherapy (to improve fronto-striatal modulation)

- Skills targeting emotional regulation and cognitive reappraisal

- Psychoeducation to reduce shame and self-blame

Strengths of ADHD

Why ADHD is present

1. The Dopamine Hypothesis in ADHD

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has long been associated with dysregulation of the brain’s dopaminergic pathways, particularly within the mesolimbic and mesocortical circuits (Volkow et al., 2009).

Dopamine is a key neurotransmitter involved in reward anticipation, motivation, and reinforcement learning.

In ADHD, reduced tonic dopamine levels and diminished phasic dopamine release contribute to difficulty sustaining effort for tasks that lack immediate intrinsic reward (Tripp & Wickens, 2008).

2. Motivation and Reward Processing

Individuals with ADHD often display “delay aversion” and reduced reward sensitivity—that is, a preference for immediate, smaller rewards over larger, delayed ones (Sonuga-Barke, 2005).

Neuroimaging demonstrates underactivation of the ventral striatum during reward anticipation, which correlates with reduced motivation and goal-directed persistence (Plichta & Scheres, 2014).

Consequently, ADHD is not primarily a disorder of knowing what to do but of doing what one knows, especially when external reward or novelty is low.

3. Dopamine, Executive Function, and Effort Allocation

Dopamine modulates the prefrontal cortex, influencing executive functions such as working memory, sustained attention, and effort-based decision-making.

When dopamine signalling is insufficient, tasks perceived as cognitively effortful or boring fail to activate motivational circuits (Westbrook & Braver, 2016).

This neurochemical mechanism underpins the subjective “interest-based” attention style often reported by adults with ADHD.

4. Dopamine Reward Pathway

One of the most significant differences between an ADHD brain vs. a

normal brain is the level of norepinephrine (a neurotransmitter).

Norepinephrine is synthesised from dopamine. Since the two go hand-in-hand,

experts believe that lower levels of dopamine & norepinephrine are both linked to ADHD.

An imbalance in the transmission of dopamine in the brain may be associated

with symptoms of ADHD, including inattention and impulsivity.

This disruption may also interfere with the changing how the ADHD brain

perceives reward and pleasure.

5. Two fundamental kinds of brain signalling in ADHD

Bottom-up signals

- Definition: Automatic, fast, sensory-driven input from the environment. Stimuli capture attention without much conscious effort.

- Brain systems involved: Subcortical circuits (striatum, amygdala, sensory cortices), the salience network, and dopaminergic reward pathways.

- In ADHD:

- The brain may be hyper-responsive to novelty and immediate rewards, leading to distractibility.

- Emotional stimuli can drive behaviour strongly, contributing to impulsivity and mood lability.

- Heightened salience detection can make irrelevant stimuli feel equally important as relevant ones.

Top-down signals

- Definition: Goal-directed control exerted by higher-order brain areas to regulate behaviour, filter distractions, and maintain focus.

- Brain systems involved: Prefrontal cortex (especially dorsolateral and anterior cingulate cortex), frontoparietal control network.

- In ADHD:

- Weaker or inconsistent regulation of attention, working memory, and inhibition.

- Difficulty maintaining focus on tasks without immediate payoff.

- Less efficient suppression of irrelevant bottom-up inputs.

The imbalance in ADHD

- Normally, top-down control dampens bottom-up noise, allowing attention to remain on task.

- In ADHD:

- Bottom-up signals dominate (novelty, rewards, emotions pull focus).

- Top-down control is underactive or inconsistent, due to differences in prefrontal networks and dopamine signalling.

- This mismatch explains why ADHD brains can be distractible in boring contexts but hyperfocused when bottom-up salience and motivation align (e.g., video games, urgent tasks).

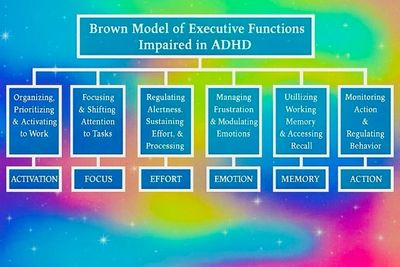

Executive Functioning

Brown, T. E. (2006). Executive functions and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Executive functions is the name given to the mental processes that people rely on to control themselves and get things done, even when they find the required task boring or tedious, and the reward for effort is delayed.

They involve the mental processes people rely on to monitor and regulate their thoughts, words, actions and emotions. They also assist people to self-motivate and take willful action, to perceive and manage time, and to direct and manage their behaviour over time.

Every time we think, we engage our executive functions — a set of cognitive processes that allow us to plan, organise, remember information, and initiate action on a goal.

Cluster 1. Activation

Organising, prioritising, and getting started on tasks

- Trouble organising tasks and materials

- Chronic procrastination, waiting until urgency/punishment to start

- Difficulty following instructions and keeping track of tasks

- Daydreaming or rushing through work

Cluster 2. Focus

Focusing, sustaining, and shifting attention

- Difficulty sustaining focus, especially for boring tasks

- Easily distracted by external or internal stimuli

- Trouble shifting between tasks when required

- Reading comprehension issues (re-reading to retain meaning)

Cluster 3. Effort

Regulating alertness, sustaining effort, and processing speed

- Good at short bursts, but struggle with long-term sustained effort

- Slower processing and reaction time

- Difficulty completing tasks consistently or on time

- Sleep regulation problems: staying up late, difficulty waking, daytime drowsiness

- Trouble persisting when tasks get harder

Cluster 4. Emotion

Managing frustration and modulating emotions

- Not recognised in DSM-5, but very common in ADHD

- Emotional reactions feel overwhelming and hijack attention

- Struggles with frustration, anger, disappointment, worry

- High sensitivity to criticism, irritability, unhappiness

Cluster 5. Memory

Using working memory and accessing recall

- Forgetfulness in daily routines (losing items, forgetting instructions)

- Hard to hold multiple things in mind while working

- Good recall for distant memories, poor short-term recall

- Struggles retrieving learned information when needed

Cluster 6. Action

Monitoring and self-regulating behaviour

- Impulsivity in speech, actions, and thoughts

- Poor context monitoring (noticing social cues)

- Trouble adjusting behaviour in real time

- Restlessness, interrupting, careless mistakes, disruptiveness

- Difficulty regulating pace (too fast/too slow)

ADHD Medication explained

Clinical Studies on effectiveness of long acting stimulant medication for ADHD

These medicines are called stimulants because they increase the brain

chemicals dopamine and norepinephrine.

They are a central nervous system stimulant prescription medicine.

These medications are Schedule 8 medicines which are subject to strict legislative controls due to their high potential for misuse, abuse and dependence.

They come in 2 forms; long acting & short acting

Long acting

Takes from 45-90 mins to work

Lasts from 8-12 hours

One a day

Doses from 20mg to 70mg

This medication is Vyvanse

Vyvanse Patient Information

Vyvanse Clinical Information

Detailed medication data can be found here

Covered on PBS $31.60 for 30 days

Short acting

Takes around 30 mins to work

Lasts from 3-4 hours

Multiple doses per day, upto a max of 8 tablets per day

5mg dose

This medication is Dexamphetamine

Clinical trials highlighting effectiveness and safety

Long-lasting medicines are usually the most practical option because people with ADHD may have trouble remembering to take their medicine.

They also provide steady symptom relief throughout the day. By contrast, if you use short-acting stimulants, your symptoms may return between doses. Some people “crash” as their short-acting dose wears off, meaning their energy and mood drop.

How ADHD medication works

In ADHD, the brain region prefrontal cortex (responsible for planning, focus, and impulse control) and their networks with the striatum and basal ganglia don’t regulate dopamine and norepinephrine efficiently.

- This leads to inconsistent attention, difficulty sustaining focus, impulsivity, and problems with motivation.

- Mechanism:

- Increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels in synapses.

- Block reuptake transporters (so neurotransmitters stay active longer).

- Amphetamines also increase release of dopamine and norepinephrine from neurons.

- Effect:

- Boosts signal strength in the prefrontal cortex, leads better sustained attention, working memory, and self-regulation.

- Reduces “background noise” in the brain so relevant information is easier to focus on.

How ADHD medication works: click here for more details

Mechanism of action of long acting Vyvanse

Studies on Safety of Vyvanse medication:

Causes of ADHD

Prenatal and Early Life Risk Factors of ADHD: What Research Says — and What Parents Can Do.

Additude Article September 2025

For most people with ADHD, many genetic and environmental risk factors accumulate to cause the disorder (Faraone et al., 2015).

The environmental risks for ADHD exert their effects very early in life, during the fetal or early postnatal period. In rare cases, however, ADHD-like symptoms can be caused by extreme deprivation early in life (Kennedy et al., 2016), a single genetic abnormality (Faraone and Larsson, 2018), or traumatic brain injury early in life (Stojanovski et al., 2019).

These findings are helpful to understand the causes of ADHD but are not useful for diagnosing the disorder.

The associations between aspects of the environment and the onset of ADHD have attained a very high level of evidential support. Some have strong evidence for a causal role but, for most, the possibility remains that these associations are due to correlated genetic and environmental effects.

For this reason, we refer to features of the pre- and post-natal environments that increase risk for ADHD as correlates, rather than causes.

The genetic and environmental risks described below are not necessarily specific to ADHD.

ADHD can also be the result of rare single gene defects (Faraone and Larsson, 2018) or abnormalities of the chromosomes (Cederlof et al., 2014). When the DNA of 8000+ children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and/or ADHD and 5000 controls was analyzed, those with ASD and those with ADHD had an increased rate of rare genetic mutations compared with controls (Satterstrom et al., 2019).

A review of 37 twin studies from the United States, Europe, Scandinavia, and Australia found that genes and their interaction with the environment must play a substantial role in causing ADHD (Faraone and Larsson, 2018; Larsson et al., 2014a; Pettersson et al., 2019).

In a genomewide study, an international team analysed DNA from over 20,000 people with ADHD and over 35,000 without ADHD from the United States, Europe, Scandinavia, China, and Australia. They identified many genetic risk variants, each having a small effect on the risk for the disorder (Demontis et al., 2019).

This study confirmed a polygenic cause for most cases of ADHD, meaning that many genetic variants, each having a very small effect, combine to increase risk for the disorder. The polygenic risk for ADHD is associated with general psychopathology (Brikell et al., 2020) and several psychiatric disorders (Lee et al., 2019a,b

Family, twin, and DNA studies show that genetic and environmental influences are partially shared between ADHD and many other psychiatric disorders (e.g. schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder, conduct disorder, eating disorders, and substance usedisorders) and with somatic disorders (e.g. migraine and obesity) (Demontis et al., 2019) (Faraone and Larsson, 2018) (Ghirardi et al., 2018) (Lee et al., 2019a,b) (Lee et al., 2013) (Anttila et al., 2018; Tylee et al., 2018) (van Hulzen et al., 2017) (Vink and Schellekens, 2018) (Brikell et al., 2018) (Chen et al., 2019a) (Yao et al., 2019).

However, there is also a unique genetic risk for ADHD.

Evidence of shared genetic and environmental risks among disorders suggest that these disorders also share a pathophysiology in the biological pathways that dysregulate neurodevelopment and create brain variations leading to disorder onset.

Very large studies of families suggest that ADHD shares genetic or familial causes with autoimmune diseases (Li et al., 2019), hypospadias (Butwicka et al., 2015), and intellectual disability (Faraone and Larsson, 2018).

ADHD Burnout

Understanding ADHD Burnout: Causes, Symptoms, and Coping Strategies

Living with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) means navigating a brain that works differently. While it comes with strengths—like creativity, energy, and unique problem-solving—it also brings daily challenges around focus, organization, and emotional regulation. Add in the constant pressure to keep up in a fast-paced world, and many people with ADHD eventually hit a wall: ADHD burnout.

This type of burnout is often misunderstood, but it’s a very real and overwhelming experience.

Let’s dive into what it is, why it happens, and how to recover when you feel completely drained.

What Is ADHD Burnout?

ADHD burnout is a state of mental, emotional, and physical exhaustion. It happens when someone with ADHD pushes themselves too hard—often trying to meet external expectations—while also managing the everyday demands that ADHD makes harder.

Some of the key drivers include:

- Constant overwhelm from tasks that feel impossible to finish

- Pressure to “keep up” with neurotypical peers

- The heavy mental load of masking symptoms in work or social settings

- Lack of rest, self-care, or proper support

Over time, this pressure adds up, leaving you feeling depleted, stuck, and hopeless.

Causes of ADHD Burnout

There isn’t just one reason ADHD burnout happens—it’s usually a mix of factors. Here are some of the most common:

Cognitive Overload

Because ADHD impacts executive function, everyday tasks like planning, prioritizing, or meeting deadlines require extra effort. That constant mental strain leads to fatigue.

Hyperfocus (and the Crash After)

When someone with ADHD locks into a task, they can work for hours straight—forgetting meals, breaks, or rest. Eventually, the body and brain crash, creating burnout.

Inconsistent Motivation

Tasks that feel boring can be almost impossible to start, while interesting ones may lead to overwork. That rollercoaster creates stress and imbalance.

Social and Emotional Stress

ADHD often comes with feeling misunderstood, judged, or “not enough.” Social interactions can feel draining, and emotional stress compounds the burnout cycle.

Masking

Trying to hide ADHD traits in professional or social settings takes huge effort. Over time, that performance is exhausting.

Sleep Struggles

Many people with ADHD wrestle with insomnia, racing thoughts, or irregular sleep patterns. Poor rest makes recovery from burnout even harder.

Signs and Symptoms of ADHD Burnout

ADHD burnout can look different for everyone, but some common signs include:

- Emotional exhaustion – feeling empty, drained, or numb

- Difficulty prioritizing – getting stuck, unable to decide what to do first

- Physical fatigue – tired no matter how much you rest

- Impulsivity – turning to quick “escapes” like shopping, eating, or scrolling

- Social withdrawal – avoiding people because it feels overwhelming

- Brain fog – struggling to concentrate, even on things you enjoy

- Mood swings or irritability – snapping over small things

- Declining performance – work, school, or relationships start to suffer

- Hopelessness – believing you’ll never “catch up”

Coping Strategies: How to Recover from ADHD Burnout

The good news is: recovery is possible. It takes patience, self-compassion, and strategies that work with your ADHD brain—not against it. Here are some steps to help you reset:

1. Recognize the Signs Early

Burnout sneaks up on you. Noticing the red flags (irritability, brain fog, emotional fatigue) gives you a chance to pause before things get worse.

2. Lower the Bar

Set realistic expectations. Perfectionism and impossible standards feed burnout—aim for “good enough” instead of “perfect.”

3. Use ADHD-Friendly Tools

- Break tasks into smaller steps

- Use timers (Pomodoro method works well)

- Create visual reminders like task boards or sticky notes

4. Build in Breaks

Schedule downtime the way you would schedule a meeting. Your brain needs recovery time.

5. Practice Self-Compassion

ADHD isn’t about laziness or weakness—it’s neurological. Speak to yourself kindly and give yourself permission to rest.

History of ADHD & ADD

ADHD vs ADD: What’s the Difference?

The term “ADD” (Attention-Deficit Disorder) was first introduced in 1980 with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) by the American Psychiatric Association. At that time, researchers believed attention difficulties could exist separately from problems with impulsivity and hyperactivity.

By 1987, however, the diagnosis was revised and the name was changed to ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) to reflect a broader understanding of the condition. With the release of DSM-IV in 1994, “ADHD” became the official diagnostic term, replacing ADD. Today, “ADD” is considered outdated, though it is still informally used to refer to the inattentive presentation of ADHD.

Subtypes of ADHD

ADHD is now recognised as one condition with three possible presentations:

- Predominantly inattentive presentation – difficulties with focus, organisation, and sustained attention, without marked hyperactivity.

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation – restlessness, impulsivity, and excessive activity without strong inattentive symptoms.

- Combined presentation – significant symptoms of both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive types.

Symptoms and Impact

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects concentration, self-regulation, and executive functioning. Common symptoms include:

- Difficulty sustaining attention and becoming easily distracted

- Forgetfulness and disorganisation

- Impulsivity in decision-making and actions

- Hyperactivity or restlessness (more noticeable in children than adults)

These challenges can affect school, work, and home life, especially in areas such as time management, organisation, persistence, and staying on task.

Grieving the diagnosis of ADHD

Working Memory

Working memory in ADHD is associated with functional differences across a distributed fronto-striatal–parietal network, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, basal ganglia, parietal cortex, and cerebellum. These differences result in impaired maintenance and manipulation of information over time, particularly under conditions of stress, distraction, or cognitive load, and account for core DSM-5 inattentive symptoms observed in adults with ADHD.

Working Memory: Key Brain Areas (and ADHD)

1. Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)

Primary region for working memory

- Especially the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)

- Responsible for:

- Holding information “online”

- Manipulating information

- Guiding behaviour based on goals and future intentions

ADHD findings

- Reduced activation and efficiency during working memory tasks

- Difficulty sustaining neural firing needed to keep information active

- Highly sensitive to stress, fatigue, and emotional load

Clinical correlate

- Forgetting what one was about to do

- Losing track mid-task

- “Out of sight, out of mind”

2.Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC)

Attention control and error monitoring

- Integrates cognition and emotion

- Helps decide:

- What to focus on

- What to ignore

- When effort needs to increase

ADHD findings

- Reduced activation → poor effort regulation

- Difficulty sustaining mental effort over time

- Increased emotional interference with cognition

Clinical correlate

- Inconsistent performance

- Mental fatigue

- Emotional dysregulation worsening forgetfulness

3.

Parietal Cortex (especially Posterior Parietal Cortex)

Storage + attentional workspace

- Supports:

- Temporary storage of information

- Shifting and updating attention

- Spatial and sequential working memory

ADHD findings

- Reduced coordination with PFC

- Difficulty updating or refreshing information

- Vulnerability to distraction

Clinical correlate

- Losing track of instructions

- Difficulty juggling multiple steps

- Problems with sequencing and planning

4.

Basal Ganglia (especially Striatum)

Gating system for working memory

- Dopamine-dependent “gatekeeper”

- Determines:

- What information gets into working memory

- What gets dropped

ADHD findings

- Dopaminergic dysregulation

- Inefficient gating → either:

- Too much irrelevant information, or

- Failure to hold relevant information

Clinical correlate

- Distractibility

- Mental clutter

- Benefit from stimulant medication (dopamine ↑ → gating improves)

5.

Cerebellum

Timing, prediction, and coordination

- Modulates:

- Timing of cognitive processes

- Predictive control

- Automation of routines

ADHD findings

- Structural and functional differences

- Poor temporal coordination of working memory processes

Clinical correlate

- Time blindness

- Poor estimation of task duration

- Difficulty anticipating future steps

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.